The right time to IPO? It's complicated.

FundersClub reviews thousands of technology startups every year, and as a VC, has backed a global portfolio of top startup founders. Our insights come from our network of top startup founders and startup investors, and from our own experiences. Christopher Steiner was a co-founder at Aisle50, YC S2011, acquired by Groupon in early 2015.

Growing startups have more ways to find liquidity now, but they still must honor tacit pacts with investors, employees.

The dearth of recent IPOs has been an obsessive subject within the tech industry. It's a topic that's even more top-of-mind for observers on the fringes of tech, as many view the IPO market as a proxy for the overall health of the tech and startup sector. And while it's true that some correlation exists between IPOs and the vibrancy of the tech market, the tendons of this relationship have grown fewer and weaker over time.

That hasn't stopped a cadre of people, some prominent, calling for more tech companies to quit raising money privately and to get on with an IPO. But declaring the need for a return to the days when Amazon went public with a $438 million valuation ignores the evolving landscape of how companies find funding and the changing demands on public companies—all of which affect how founders, who ultimately are still in control, view IPOs. The answer to this question—when should a company IPO—is one that has to ebb and flow with capital markets while also respecting the implicit pact around liquidity that exists among founders, their investors and employees.

IPOs remain the ultimate liquidity valve for all parties: investors, founders and employees. But whereas the IPO was once something of a regimented step in a growing tech company's evolution, it is now simply an available option, albeit one whose likelihood of being implemented grows with a venture-backed company's age.

As the financing options for growing companies have broadened, the path to an IPO has changed indelibly. A recent McKinsey & Company report shows that tech companies now stay private for three times longer on average, and more than 50% of tech companies hit the public market as profitable enterprises, compared with less than 10% from 2001 to 2008. And the cash pile available for private companies continues to grow. Last year ended with venture funds having amassed $150 billion of committed capital that has yet to be invested, an all-time high.

The Pact

Venture capitalists typically have 10-year windows on their funds. LPs enter their investment covenants with an expectation that the fund will be winding down, if not totally divested, at the end of that decade. It’s a tenet that’s consistent across most of the industry. None of this, of course, is an absolute. Funds often possess investments past the 10-year mark, but there is an understanding between VCs, LPs and, on a lesser level, founders, that funds aim for an overall liquid position after 10 years.

The other formative cog in liquidity considerations: employees. Founders strike deals with their team members to build toward the same goal, pushing an operation from its formative stages to a greater version that could well be listed on a public stock exchange. Many startup employees, especially early ones, make a deliberate choice to earn less in the short term in exchange for the chance to own more of the company they’re helping to build. In many cases these early employees grow up with the company and become, along with the founders, keystones of growth and operations. They’re the most valuable people at the company.

With that in mind, founders need to honor the pact they’ve struck with their employees, just as they do with their investors. If the team has succeeded in building something exceedingly valuable, founders need to find windows of liquidity to reward the people with whom they’ve built the company. Deferring this can get troublesome. Palantir, founded in 2004 and now valued at $20 billion, while eschewing an IPO, has reportedly felt increasing pressure to search out more opportunities for employees to sell some of their shares in the company.

An IPO is unique among exit options in that it satisfies all parties’ needs for liquidity while also allowing employees, investors and founders to continue betting on the company by holding shares. Venture capitalist John Doerr, for instance, still owns Google shares more than 11 years after its IPO, and many other VCs held onto their shares for years after the event (Doerr is currently on the Google board). Unlike IPOs, acquisitions, although they are liquidity events, put an end to the upside for the invested players.

But markets have greatly evolved during the last several years so that liquidity events are no longer the binary scenarios of acquisition, IPO or hold. Palantir hasn’t seen a major liquidation event, but it has on occasion been able to find release points of liquidity where employees and investors can divest some portion of their stock, whether that’s during a new fundraising round or the chance to offer shares on secondary equity markets or to buyers such as Millennium Technology Value Partners. To be sure, these aren’t opportunities to sell large swaths of stock or a majority of one’s holdings, but these instances do allow founders to preserve the pact on some level, to buy time and to give VCs and employees the chance to gather some winnings.

It’s true that alternative means to liquidity at some level have existed for years. Millennium Technology Value Partners, one pioneers of liquidity solutions for private venture backed companies, invests directly as well as through secondaries. For its secondary strategy, it buys existing shares from founders, employees and early investors by working directly with the companies’ management. Millennium has been making such investments since 2000, and it has worked with a wide range of companies, from Facebook and Twitter to Spotify and Pinterest.

Ray Cheng, a principal at Millennium, says the flexible nature of his fund’s approach can help companies delay an IPO to a time when the public market may be stronger and more receptive to new issues. “Many of the top private companies need another year or two of sustained high growth to determine if the public markets will validate the high valuations recently set by their private financings. There are profitable companies waiting and hoping for improved market conditions to go public. In the meantime, some of their constituents desire or need liquidity.”

IPOs aren’t very indicative of tech industry health

Buying time, while it sounds anathema to the desire for an exit that most investors seek, has been integral to the liquidity game since the beginning. “Part of the upside opportunity is the patience required to get there,” says Howard Hartenbaum, a general partner at August Capital.

Hartenbaum also points out that the average exit requires 9.6 years, a duration that offers IPO-seeking companies the opportunity to time the event to their liking. Some companies that draw investments in year two or three of a venture fund could take 10 to 12 years to reach a major exit, putting that event 15 years beyond the fund’s opening. Through this lens, companies such as Uber and Airbnb still appear quite young.

And with exit windows so wide, companies tend to pick their moments carefully. One thing that many of those decrying the lack of tech IPOs fail to acknowledge is that public offerings are sometimes less indicative of a company’s health and position than they are of lagging trends in the public stock indices.

Tech IPOs often come in flurries because of the perception, right or wrong, of how public markets will accept (price) them. So in this way, the IPO has never been a true measure of where a company is at; it's a liquidity instrument that's pegged to overall market health, not that of the tech sector.

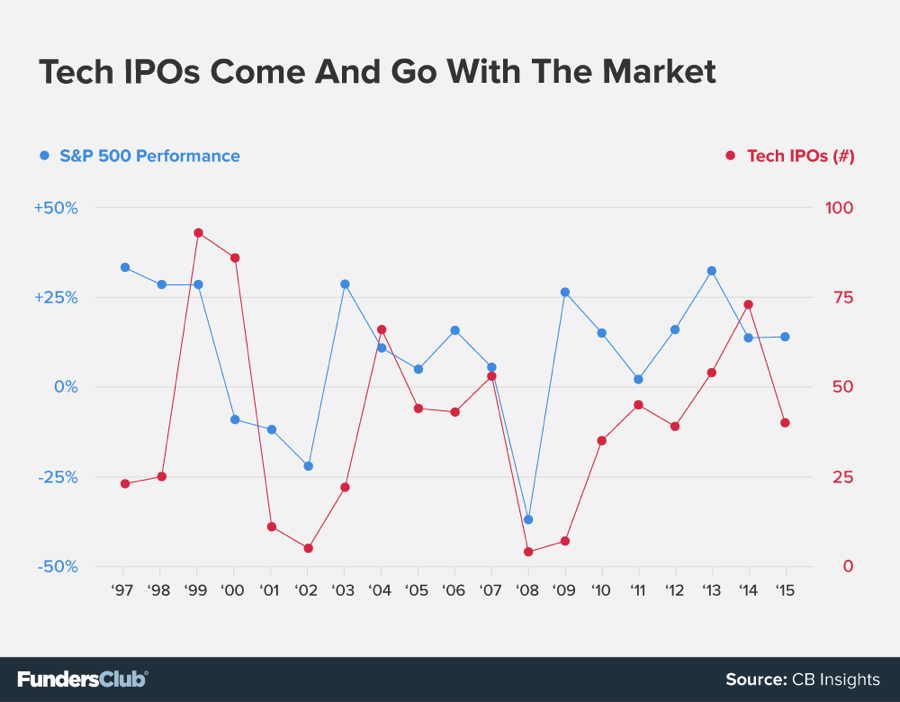

We evaluated tech IPO data from CB Insights compared with the performance of the S&P 500 starting in 1999 until now, revealing a somewhat predictive relationship. Tech IPO activity is highly correlated with positive performances by the S&P 500. IPOs tend to lag market activity by a quarter or two, so that large slugs of IPOs follow particularly good periods for stocks. Consider that 2008 and 2009 brought just four and seven tech IPOs, following a dismal time for the market, which lost 37% in 2008 after gaining just 5.49% in 2007. But during 2013, the S&P gained 32.4%, helping push out 73 tech IPOs in 2014

In 2015, the S&P gained just 1.4%, but the third quarter was particularly tumultuous, as the index dropped 5.6%. Then, during the first three weeks of 2016, the S&P lost 9.03. It’s upon this backdrop where we went an entire quarter, Q1-2016, without a tech IPO—only the fourth time that’s happened since the early 1990s. The market has seen a couple of tech IPOs in the second quarter, including Acacia Communications, a profitable maker of components for fiber optic networks whose share value jumped more than 30% on its first day of trading on May 12. But Acacia remains an outlier at this point.

Clearly, tech IPOs have more to do with how underwriters and companies perceive the buoyancy of the market versus the actual prospects of the company and inflection points that it may have cleared. Bill Gurley worries about emotional biases twisting incentives in the private market, but those anxieties are just as active in the public market.

Wall Street v. the private market

Companies can grow dominant and efficient without going public. The largest private company in the United States, according to Forbes, is Cargill, a Minnesota food producer and distributor, with $120 billion in revenue. Exit pressure is an alien premise for Cargill, as it’s still majority-owned by its namesake family and was founded more than 150 years ago.

For the venture-reared companies of today, however, exit pressure is real. Companies can ignore it for a period when attempting to time their exit with the swings of the market, as they clearly do. But the more common stated reason to remain private is to operate free of the quarter-to-quarter scrutiny brought by public shareholders and the media.

The question: Can companies more efficiently build value being private rather than public? People like Peter Thiel, a co-founder at Palantir, and Travis Kalanick, the CEO at Uber, clearly think so, although Kalanick also acknowledges what he calls a moral obligation to find liquidity for investors and employees.

Would Amazon or Google be worth more right now had they decided to stay private for longer periods? It’s impossible to say, although both companies have found lots of ways to innovate and expand into new spheres as public companies.

Much of the current worry among VCs is that the current trend of high-priced late rounds, like the one that recently valued Uber at $62.5 billion, will make it difficult to achieve equal or higher valuations in an IPO.

"I question whether Uber, Airbnb and other private companies that raised large rounds at huge valuations will be able to sustain those valuations and achieve IPOs at markups from the last rounds,” says Bruce Barron, partner at Origin Ventures, which led early rounds at GrubHub, which IPO’d in April 2014. “I am fairly doubtful that most will succeed by this standard."

But whereas Barron, Gurley and others call for these companies who are holding out to just get on with it—Fred Wilson, who agrees, had choice words on the matter—there’s no guarantee that Wall Street will price post-IPO shares any more fairly, high or low, than the private market. In 2012, Facebook IPO’d at $38 a share and during the next 12 months dipped as low as $19, a 50% drop, before going on its long current run toward $120. Twitter IPO’d at $26 in November 2013, raced to $60 by the end of the year, and was at $30 just five months later. It’s now $14. Today’s high prices for private rounds could easily be seen just as Twitter’s run to $60 was in the public market: part of normal market machinations, but private.

Here’s where Gurley’s argument for down rounds without shame makes a lot of sense. And perhaps such rounds will come to pass for the current class of large privates, as VCs will likely dispense plenty of capital during the next several years, having just had the biggest fundraising quarter in a decade.

IPOs represent different things to investors and founders

There will always exist a divergence in outlooks on IPOs. For Mark Zuckerberg and Jeff Bezos, the IPO was simply a liquidity event in the middle of their company’s evolution. Many investors see the IPO, however, as an end to the journey, an ultimate goal. They want the journey to end because it’s here that returns are booked and gains distributed to LPs.

The unicorn class has taken private money because it’s been there at great valuations, points out Josh Kopelman, partner at First Round Capital. “The reason why the IPO market has been stagnant is because there is a massive disparity between the prices that private companies can get funded at and the prices that public companies trade at,” he says. “As a result, many large private companies are reluctant to go public out of fear that they would trade at a meaningfully lower price.”

Companies like Amazon, reared in the late 1990s, didn’t even have these IPO alternatives because such large amounts of private capital simply weren’t available.

The larger these private rounds get, the more they begin to simulate public markets. They can be bubbly or they can express angst in the form of the down round. It just so happens that having a public down round—watching, along with the rest of the world, your share price tumble on a live ticker—is currently a more acceptable option within the industry than going through a private down round, when your share prices tumble in leaked reports and news articles.

The fact remains that, for founders, the tacit pact to find liquidity needs to be fulfilled. Those investors with late money in won’t find the liquidity nearly as fulfilling as those with the earlier money. But that’s not dissimilar from dismay experienced by whoever bought those $60 Twitter shares, a group largely comprised of retail investors—not the billionaire venture capitalists who topped off Uber and Airbnb. Both investor groups, the public Twitter ones and the private VC ones, came late, after the big gains had been booked and, for now, they lost.

Just like technology, the financial vehicles that enable its construction remain in flux. As long as tech companies find funding through wide consortiums of disparate investors, the biggest successes will require an exit via public markets or through an acquisition by an even larger and already-public company.

Because an IPO inherently represents different things to investors and founders, there will always exist the possibility for a rift on when it should happen. At the moment, changing capital markets, a horde of available private capital and a downward trend in the overall stock market have conspired to drive that rift to its widest point ever.