The Right City Can Give Your Startup a Better Chance at Success

FundersClub reviews thousands of technology startups every year, and as a VC, has backed a global portfolio of top startup founders. Our insights come from our network of top startup founders and startup investors, and from our own experiences. Christopher Steiner was a co-founder at Aisle50, YC S2011, acquired by Groupon in early 2015.

When Mark Zuckerberg moved his nascent company from Boston to Palo Alto during the summer of 2004, he wasn’t following the mandate of an investor or board member, he was simply acknowledging the gravity of Silicon Valley. He wasn’t even sure if he’d stay.

Facebook found great investors in California—Peter Thiel, Jim Breyer—and Zuckerberg never returned for his junior year at Harvard. But he did later remark that, if he were doing it all again, he wouldn’t have moved Facebook away from Boston. That one of the most successful startup founders of the last 20 years would publicly question his location decision shows how integral this question is for most founders. It’s something they grapple with from the start.

Paul Graham has continually made the case to Y Combinator companies to stay in the Bay Area, and believes that the advantages offered in Northern California are as relevant as ever, but he says that some other startup hubs, notably New York City, have made up ground.

Zuckerberg can easily second-guess his choice because it’s likely he could have lured the same caliber of investor whether Facebook was in Boston or Palo Alto, as the company was exhibiting incredible growth. The average startup—even those that eventually raise $1 million or more—doesn’t have the options that Zuckerberg had. The question of location can boost a startup toward success or doom it to also-ran status.

So given a choice, where should founders look to locate their startup?

As with most simple questions posed toward a group as large and varied as startups, the answer is anything but simple. Companies must consider a coterie of variables when weighing this question:

- Funding

- Where a company is in its lifecycle

- Skills and networks of founders

- The startup’s industry

One of the keystone variables for any early startup that isn’t yet profitable, obviously, is money. With it, the startup can live on, build and get better; without it, the startup will eventually fail.

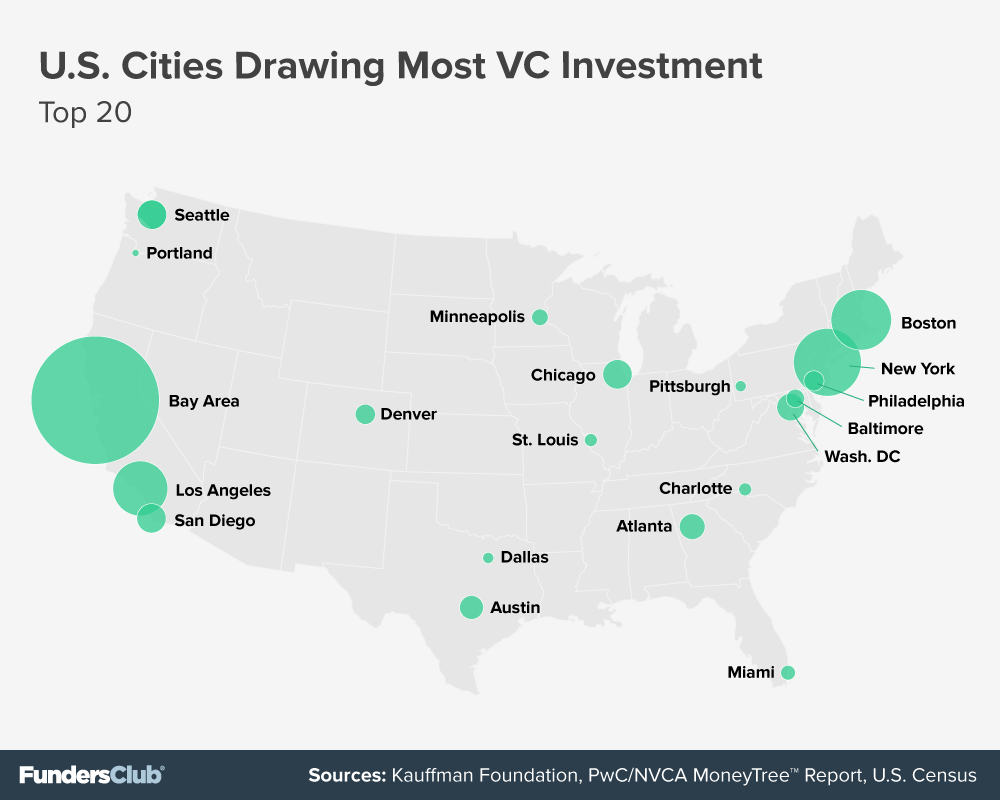

Data show that the money case today still breaks mostly in favor of major startup hubs, primarily the Bay Area:

There exist all kind of lists and datasets that track to whom and to where venture capital flows. The Bay Area still dominates in the overall amount of funding, capturing 40% of the total venture capital dispersed within the United States. But many things affect that number, including the fact that most of the exceedingly successful venture-backed companies already reside in the Bay.

These companies, like Uber, Airbnb, and Palantir, draw large late-stage rounds whose total dollar value can trump the combined value of dozens or even hundreds of healthy-sized seed and A rounds. Those larger late venture rounds and their influence on the statistics don’t help us answer the important question:

Where does a startup stand the best chance of getting funded, all other things being equal?

To answer this, we need to be able to quantify in some manner the number of startups in a metro area and the number of startups that draw funding in that metro. No totally clean and public datasets exist on this, but there are resources which allow us to make some reasonable representations of this relationship.

Using the Annual Kauffman Foundation Report, we can glean Startup Density—the number of startup firms per 100,000 people—for all of the major metropolitan areas in the United States. Kauffman defines a startup as a company that is less than one year old and has at least one additional employee to the founder/owner. So this measurement will capture businesses that may not be of the type that can or will ever draw major venture capital investment—like a coffee shop (unless it’s Blue Bottle or Philz Coffee)—but it also eschews counting one-man consulting shops and more established startup companies.

Cross-referencing that list with normal U.S. census data yields the number of startups in a given metro. According to this data, New York has the largest number of new startups at 37,054, followed by Los Angeles and Chicago, which makes sense given these are the Nos. 1-3 largest metro areas in the United States. The Bay Area comes in at No. 4 for total number of startups. So while there may be more software-focused startups founded in a given year in the Bay Area than in Chicago, the number for the latter city is bigger because Kauffman is counting all new small companies with more than just a founder(s).

As for startup investments, the total number per metro can be found in data from the PriceWaterhouseCoopers/National Venture Capital Association MoneyTree Report. This report also makes a distinction between the total number of investments and the total number of companies that drew funding, as some quickly growing companies may land more than one round of investment in a single year. So the latter number here, the total number of companies drawing funding, is most interesting.

Having that figure in hand for the largest 40 metro areas, we can divide it by the total number of startups in a given metro (derived from Kauffman’s startup density figure and census data). The results provide an interesting figure for examining what percentage of startups receive funding in a given metro.

This isn’t a perfect measurement. Younger startups in up-and-coming cities often have only attracted angels, leaving them out of these stats, and some of the more established startup hubs are rife with startups that have been around three or four years and have an easier time attracting funding.

The Bay Area comes in at No. 1 on this list, with a ratio of 11.2% of companies funded divided by the number of startups. It’s a steep drop to Boston at No. 2, with 5.65%. More interesting is Pittsburgh at No. 3, at 3.59%. A caveat with Pittsburgh: of the 40 metro areas examined, it carries the second-lowest startup density, only ahead of Cincinnati. So for its size, Pittsburgh has a well below-average number of startups. This is likely due to the age of the population in Pittsburgh’s metro, which is old, with a median of 43 years, compared with metro areas of San Francisco-San Jose, whose median is 36.6 years, Chicago at 36.8 years, New York at 37.9, Boston at 38.7, or Los Angeles at 36.1. With a higher percentage of retirees and people aged past 50, there are fewer people likely to found a startup in Pittsburgh.

Pittsburgh also has a very low average investment size, at $2.1 million, multiples less that of the Bay, at $20.6 million, or many other cities drawing larger amounts of venture capital, such as New York, whose average investment is $14.6 million or Chicago at $12.7 million. The next three up in terms of funding percentage, after the Bay, Boston and Pittsburgh, are: Austin, San Diego and Seattle, at 2.6%, 1.8%, 1.7%.

The overall average across the top 40 metros is 1.4%, but that’s heavily affected by the Bay Area’s 11.2%. The median among the metros is far less, at 0.68%. So, by the numbers, the money component favors startups in the Bay Area, as a higher percentage of them find funding. There are a number of factors that affect these figures, of course. The Bay recycles experienced entrepreneurs with deep networks from its own ranks of engineers and workers, and it also draws new entrepreneurs, often of the most determined type, who leave their old lives behind to build something in the Bay. This is a positive selection process that continually feeds the Bay Area machine.

For new startups with serious founders bent on building a great product, being in the Bay will heighten the chance of being funded, for all of the reasons above, and because investing, like most business endeavors, is built upon relationships, proximity, and the path of least resistance. For Bay Area venture capitalists, which, in terms activity and number of investments, account for eight of the top 10 VC firms in the United States, investing within the region they inhabit has been and will continue to be a virtuous cycle.

But other factors, especially for founders who are rapidly scaling up, make the case for San Francisco or Silicon Valley less clear. Fledging startups’ primary challenge may be finding funding, but once companies have hit upon a channel and product gaining rapid traction, the critical path often depends on hiring enough of the right people. The depth of technical talent in the Bay Area has no rivals anywhere in the world. But hiring talent in the Bay also costs more money and effort than it does anywhere else.

Scaling Up, Hiring Rapidly: Unique Benefits, Challenges In The Bay

For young companies that have found funding and have a well-defined mission, there’s nowhere better to build than the Bay, says Max Mullen, co-founder at Instacart. “There’s a value that’s hard to quantify being here in Silicon Valley,” he says. “But one of the critical advantages to being here is the talent you’re able to hire.”

And as a young company that’s small and nimble, Mullen says, you can offer people something that bigger companies can’t: a chance at meaningful ownership and the ability to see one’s work show up in the product in major ways very quickly.

But recruiting can become trickier when companies go past 50 people and have lost the appeal of being small. We spoke with several founders with significant businesses who thought that the Bay Area offered an ideal setting for incubating a young company, for finding that spark and the early capital that gets the enterprise rolling, but that a second-tier startup hub, like Austin or Chicago, offered better opportunities to scale the business and build a quality team while preserving more capital.

Mark Lawrence, CEO of SpotHero, thinks being based in Chicago has given his company a form of arbitrage on talent and fixed costs compared with companies based in the Bay. When he started the company with cofounder Larry Kiss, they asked themselves the question: “Should we move to New York, should we move to San Francisco?”

The pair stayed in Chicago and has since raised $27 million from investors in their town as well as both coasts. Developer salaries in San Francisco can commonly be 30% higher and more than in most metros, and finding good engineers in other places offers some relief, but Lawrence says a hidden benefit of being outside the Bay is the price of hiring non-technical talent. In Chicago and other cities, entry-level graduates in marketing, HR or sales can be hired for $40,000 or less. In the Bay, the number is often closer to $65,000, simply due to the cost of living. The benefits required in the Bay, things like free catered lunches and chartered transportation to work, can drive the real cost even higher, meaning that the costs to employ young non-developers at Bay-area companies are double those elsewhere.

“I’m surprised a company hasn’t moved from San Francisco to Chicago,” laughs Lawrence.

As a Bay Area company, thredUP, an online consignment shop that has raised $125 million, has to pay higher salaries for developers. ThredUP’s CEO James Reinhart says that, for a young company starting out in the Bay, the task is manageable because the company can offer a newness and a sense of getting-in-early, which greatly appeals to some engineers who are willing to take lower salaries for that benefit. It gets harder a couple of years in, Reinhart says. “There is an 18-month period where you’re no longer brand new, and you don’t yet have the cachet or profile to hire a lot of the best senior people”, he explains. “We’ve crossed the chasm now, though, but everybody here has to compete hard for those better engineers.”

It’s not only the people that cost more in the Bay, as office leases regularly top $75 per square foot per year. Despite that, Reinhardt still believes it’s the best place for young entrepreneurs. “The cost of failure here is lower, because there are so many companies doing interesting things,” Reinhart says. “If your idea doesn’t work out, you can go to Twitter or Facebook or Google and plan your next move.”

Google cofounder Sergey Brin recently said that companies are better off starting in places other than the Bay Area, because during the tech boom periods, high costs and high employee expectations—which can lead to job-hopping—make things very difficult on new startups. It’s during the rapid scale-up phase where Brin thinks the deep pockets of Silicon Valley come in most handy. Although it’s also true that Bay Area VCs don’t discriminate according to location if a company has found traction; they’ll fund companies anywhere.

There exist few actual cases of startups packing up and leaving the Bay, but some are looking to a kind of hybrid model, where the company is founded and established in the Bay, but as it grows, opens other offices, especially for engineers, outside of Northern California. Thunder, a creative platform for ad creation based in San Francisco, seeks to hire 20 people, many of them engineers, in its Seattle offices this year. That will move its Seattle headcount, which is already at 30, past that of its San Francisco base. The company has raised $11 million.

The Bay Area is still the best place to start a company, says Thunder CEO Victor Wong, “But you grow to where your best supply of talent, customers, and capital exist to fuel your growth.”

Founders Should Leverage Current Networks & Locations

In a vacuum, San Francisco and Silicon Valley still provide the best pad for building a company, says Nicholas Chirls, a partner at New York’s Notation Capital. “Anybody who argues that there is a better overall place is just wrong,” he adds. “But you can build a big company pretty much anywhere, that’s been proven.”

Moving everything to California shouldn’t always be done at the expense of good networks and support structure elsewhere. For early founders still building out an early version of their product, staying close to home and incurring as few expenses as possible will always be a prudent strategy. Moving to the Bay—or any other startup hub—should be a step taken when founders have experienced some legitimate traction.

Even with that traction and a bit of funding, founders will find hiring technical talent difficult, especially in the Bay, warns Patrick Gallagher, general partner at Crunchfund. “If you are starting a company and can't make your first 3-5 relevant technical hires through the founders' own personal networks, then you are at a huge disadvantage,” he explains. “If you start a company in a market that has good access to capital at all stages, like New York or Los Angeles, and your technical network is in those cities, then don't move to Silicon Valley. You'll end up spending all your time networking and recruiting to hire technical talent. We've seen many of our portfolio companies move to Silicon Valley and struggle with recruiting.”

Gallagher thinks that companies who are not in markets that have deep pools of venture capital typically need business metrics 2x better than similar companies in the Bay to draw comparable funding. “It’s hard to get early stage VCs on a plane,” he says.

But that is changing. More Bay investors are taking a wider view geographically as to where to place their capital, says Erik Rannala, cofounder and managing partner at Mucker Capital in Santa Monica, Calif. “The money is starting to flow outside of the Bay Area to other places, so getting funded is becoming less of a problem, which is great for places like L.A. where there is a ton of technical talent that isn’t as expensive as in the Bay.”

Rannala sees his position as a Los Angeles-focused investor as advantageous, describing the area—or any area outside of the Bay—as underinvested. Chirls, the VC from New York, sees things similarly. “We love being in New York because there’s so much less competition, there’s just not that many firms that we compete with.”

There can be a limit to how much a local market can support, no matter how connected the founder. Josh Dziabiak felt that boundary when he started working on The Zebra, a consumer platform for car insurance quotes, with his cofounder Adam Lyons. Dziabiak founded his first company, a web-hosting platform, when he was 14. He sold that when he was 17 and went on to found Showclix, a ticketing application for midsize venues and events that Dziabiak grew to more than $100 million in sales after raising $6 million in venture capital. He did all of this in his native Pittsburgh. But taking on the $1 trillion market for car insurance required bigger stores of capital and technical talent than Dziabiak thought Pittsburgh could provide.

The cofounders moved The Zebra to Austin, where they eventually raised a $17 million A round from Silverton Partners, Ballast Point Ventures, Mark Cuban, and others. They considered New York and San Francisco, but felt that the tech talent in Austin was deep enough for their venture and the cost savings were too big to ignore. “My natural inclination is to tell people to go to a second-tier or third-tier city,” Dziabiak says. “There is a big delta in the cost of living from San Francisco to Austin.”

San Francisco startups do enjoy an edge with the media, however, Dziabiak believes, a factor that should be considered for consumer-facing businesses.

Industry Centers of Gravity Still Matter

Companies zeroing in on an industry that congregates around one or two cities should consider picking up and moving to those places. Being part of the native ecosystem, getting familiar with incumbents and building a strong industry-specific network benefits any business. Founders focusing on the fashion industry, for instance, should consider New York; startups trying to break into trading or finance markets should likewise consider New York as well as Chicago, where the next generation of electronic trading houses and brokerages are based.

Reinhart, of threadUP, sees the Bay Area as a natural fit for founders looking to create the next big social platform. For those looking at hard and medical sciences, he thinks Boston makes more sense. For retail plus tech, Reinhart says other cities, like New York and Seattle, offer good opportunities.

Some companies glean an attitude and edge provided by the city they’re in. Chirls names Kickstarter and Etsy as companies, conceived and reared within the New York artist community, that have the boroughs in their DNA. Being in the city that is the nation’s center of design and art helped these companies reach keystone designers, artists and curators; when this group jumps onto an online platform within the space, others follow.

Likewise, companies piling into cloud computing or developer tools need to look at the Bay, reasons Eric Groves, the CEO of Alignable, a social network for business owners. But founders who put down roots in the Bay, Groves says, have to realize that access to California capital and customers comes at the cost of higher burn rates and tougher talent battles. Alignable is based in Boston and has raised $11 million, including its latest round of $8 million, which was led by Mayfield Fund, a Sand Hill Road VC firm.

“Tech startups, like any business, end up revolving around critical resources: customers, capital and employees,” Groves says. “Finding the place where you can unlock access to all three of these things gives you the best chance at success.”