International Venture Capital Will Soon Pass That Of United States

FundersClub reviews thousands of technology startups every year, and as a VC, has backed a global portfolio of top startup founders. Our insights come from our network of top startup founders and startup investors, and from our own experiences. Christopher Steiner was a co-founder at Aisle50, YC S2011, acquired by Groupon in early 2015.

During the heady days of the tech bubble in the late 1990s and the early 2000s, venture capital was a decidedly American institution. Its existence and placement was thin outside of California, and nearly nonexistent outside of the United States. It remained that way for years. But during the last decade, global venture capital and the startups it fuels have crept toward equal footing with the United States.

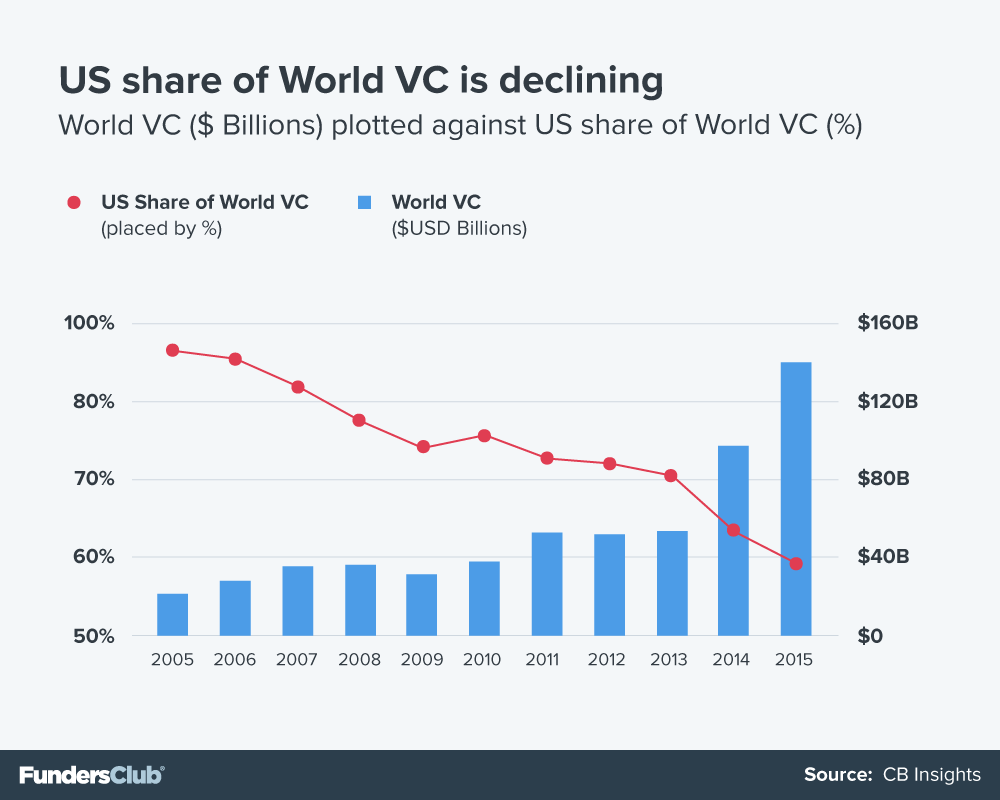

In 2015, United States startups still received 59% of the global venture capital pie, but ten years before that, in 2005, American startups garnered 94% of all venture capital. For non-U.S. startups, narrowing that gap in just 10 years is all the more impressive because it's come during a time when U.S. venture capital aggressively scaled up.

From 2005 to 2015:

-

U.S. venture capital increased 4.1x, from $20.1 billion to $83.2 billion.

-

VC outside the U.S. increased 43.9x, from $1.3 billion to $57 billion.

Worldwide, 2015 was easily the biggest year for venture capital placed during the last 10 years, totaling $140.2 billion.

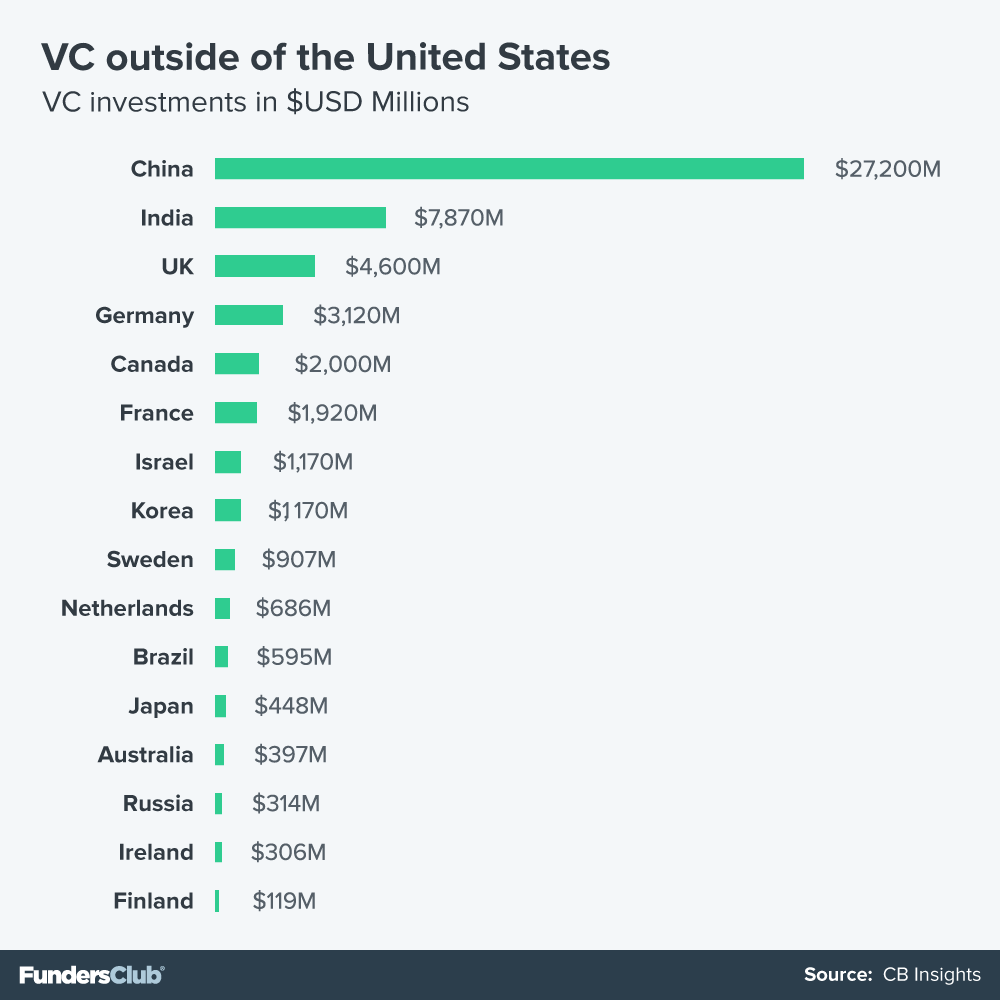

And unlike the earlier days of U.S. venture capital, where most of the money went to California companies, global VC money hasn't been concentrated in one place. Leading cities and countries have emerged, of course, but the capital is spread out across wide swaths of geography, from Asia to Europe—and there are positive signs in South America and Africa.

Abroad, governments play more active role.

In Europe, the venture capital movement includes all manners of investors, from seed stage funds like 500 Startups, which attracts many European founders, to major institutional VCs such as Accel and others like them with European roots. It also includes, unlike the United States, an outsized number of investments from government-sponsored funds.

Some that were active in 2015:

Innovate UK: 18 investments

Enterprise Ireland: 11

Portugal Ventures: 27

Scottish Investment Bank: 22

London Co-Investment Fund: 17

Investment through public-related entities such as these helped the European ecosystem get off the ground from almost nothing ten years ago.

The situation in China is similar but government entities there, from the national level to the provincial and local level, have amassed a cash pile unlike any other. According to Bloomberg, government-sponsored VC entities in China now have $339 billion to spend on tech companies. Just this April, a government fund led the $4.5 billion investment round into Alipay.

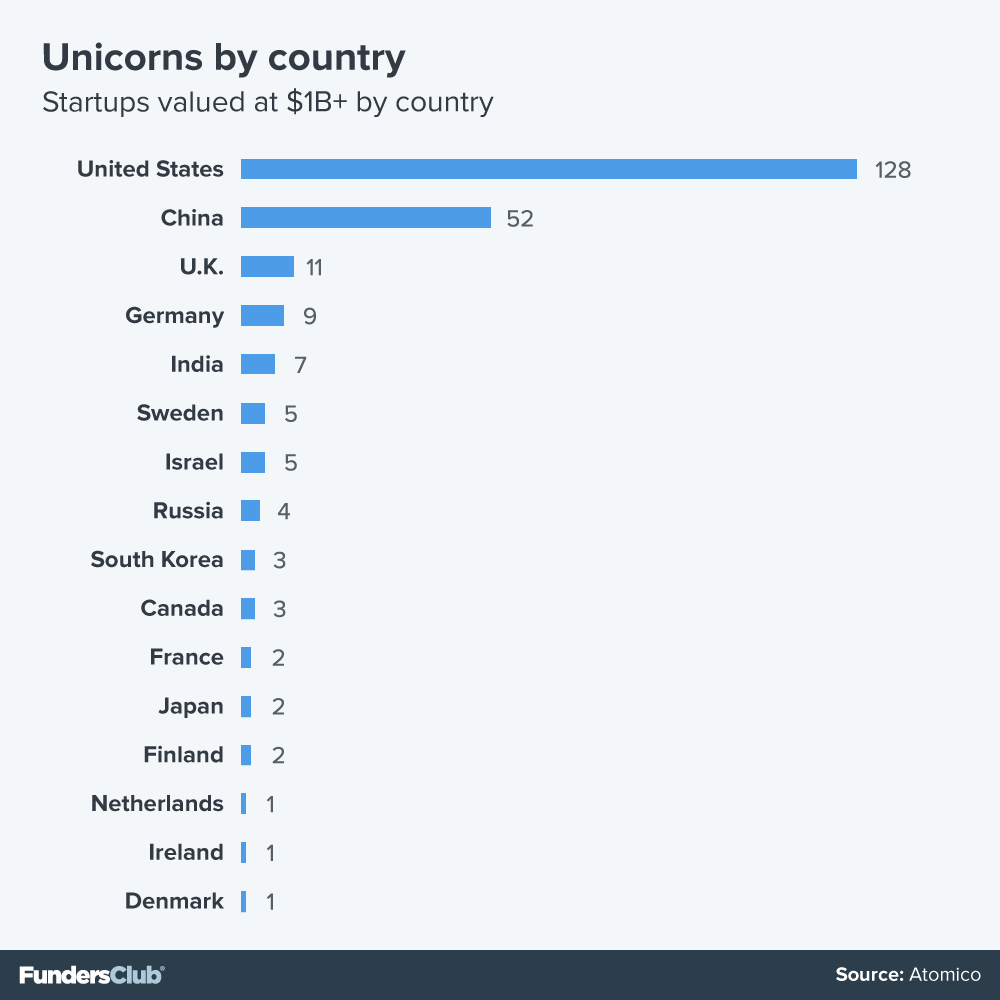

It shouldn't surprise then, that China’s total of 52 unicorns places second only to the United States, with 128, and is 4x the total of the next closest country, the U.K., which has 11. With so much money at the ready and the largest web economy in the world, in terms of users, China will likely continue to close the gap on the United States.

Advantages to NOT being the United States.

Startups kindled outside of the United States and Canada have one main advantage: they’re likely focused on a global market from the beginning. Other than China, there is no single market that compares to the size and breadth of that of the United States. So a startup coming from Finland or Brazil that has major aspirations will be thinking about markets and success outside of its native country right away.

Startups within the EU have easy and natural access to a large, mostly-unified market early on, and successful companies here usually spread quickly within the EU footprint.

Weiting Liu is a veteran of both Y Combinator and Techstars and his newest company, Codementor, which offers live coding help to developers, has offices in Taiwan as well San Francisco. While Taiwan has a good base of developing talent, the market itself isn’t big enough to foster multiple unicorns that are primarily focused just at home. During the last five years, Liu says, Taiwan has spawned several companies that have found quick traction abroad.

Not being based primarily in the United States gives Codementor two edges, he says:

- It's a way for Codementor to hack the hiring war in the Silicon Valley. Instead of competing against Facebook, Airbnb, etc., to hire top engineers, the company can tap an bundant supply of great engineers in Taiwan who are on par with the talent in the United States, Liu says, and much more loyal.

- Being in Taiwan allows Codementor to see things outside of the Silicon Valley bubble. Half of the mentors on Codementor are based outside of the United States, and not all of them think like SV engineers who have worked at Google or Facebook, which is helpful when trying to address a global market.

The United States will remain king, but its share will continue to shrink.

Software has been part of other countries’ economies for decades—SAP was formed by five former IBM engineers, all German, in 1970. But as software intermixed with the web, beginning in the mid 1990s, non-U.S. countries fell behind in developing new applications. There are several reasons for this, but perhaps the main one is that Europe and the rest of the world was missing a ready and deep supply of capital willing to take on the major risks of funding these new kinds of companies.

After the dot.com bubble popped, many across the world saw even more reason not to emulate the kind of venture infrastrtucture that existed in the United States. But having that capital and that expertise still on hand, ready to be deployed, gave American tech startups a giant edge, as the country churned out Facebook, Airbnb, Dropbox, Twitter, Uber and others during a time when the rest of the world was left flat-footed, with little capital to fund engineers and founders who were working on new products. Some exemplary founders—such as Niklas Zennström of Skype—broke through, but the hits were still rare for non-U.S. startups.

But the world is clearly catching up—rapidly—as the United States’ startups share of the world’s placed venture capital will likely dip below 50% within three to four years.

Part of this evolution is simply the maturing of economies in countries such as China and India, where enormous populations continue to pile into mobile and the web. Companies based in those places, while they may be behind U.S. companies from a technical standpoint, have a large edge in being part of the native landscape and endowed with an inherent understanding of their home markets.

But much of this change is simply a world-over realization that well-placed venture capital can bring outsized returns compared with other asset classes, and that having more of that capital deployed increases the chances of unicorn-style successes. And it’s these kinds of companies that can help push an economy forward during a time when growth from traditional sectors lags.