Your Money in 20 Years: The Future of Robo-Advisors

Will startups be able to unseat giant incumbents who have started their own automated investing platforms?

Up until several years ago, the investment industry was one of the few giant markets that had yet to experience true disruption from technology startups. But with the proliferation of robo-advisor firms, that has changed. VCs have poured money into startups in this space, as they've taken aim at the old guard companies who typically hold and manage investment and retirement accounts.

The total assets under management by robo-advisors remains small, less than $200 billion, and that’s including robo-products belonging to big existing companies. The investment industry as a whole in 2015 totaled $64 trillion in assets. But some projections show robo-advisors' share growing to $20 trillion by 2020. Even at a declining growth rate from there, it's feasible that half of the industry could be in robo-controlled accounts within 15 years.

That may be an aggressive forecast, but it shows how the impact of these newer companies goes far beyond the total assets they currently manage. They have sparked major change in the industry and forced many of the incumbents—like Schwab, Fidelity and Vanguard—to create new products.

It could be argued that the robo-advisor movement has even accelerated regulatory movements aimed at limiting the kinds of kickbacks and commissions that financial advisors can earn while managing retirement accounts, as the Department of Labor has created its "fiduciary rule," scheduled to go into effect in April 2017 if it's not scuttled by a bevy of lawsuits mounted by financial industry groups.

Most of the effects of these recent changes to the investment business have proven beneficial to consumers. As the early startup players like Betterment and Wealthfront grew, dozens of other startups jumped into the race, including those focused solely on 401ks—Human Interest — or even those that pitch directly to women (Ellevest). But now with robo-advising turning into arguably more of a feature than a product, as incumbents have all put down stakes in the space, the question is: where will your money be in 20 years?

Will the startups who invented the space be able to capture a significant share of the coming inflows—or will they be walled off by the incumbent companies who have jumped in?

The benefits of robo-advising, just like the benefits of automatic contributions for savings and retirement accounts, are borne out by data. The move toward more transparency in the space, the percolating DOL rule and the vertical rise of index funds all point toward robo-advising becoming something of a standard.

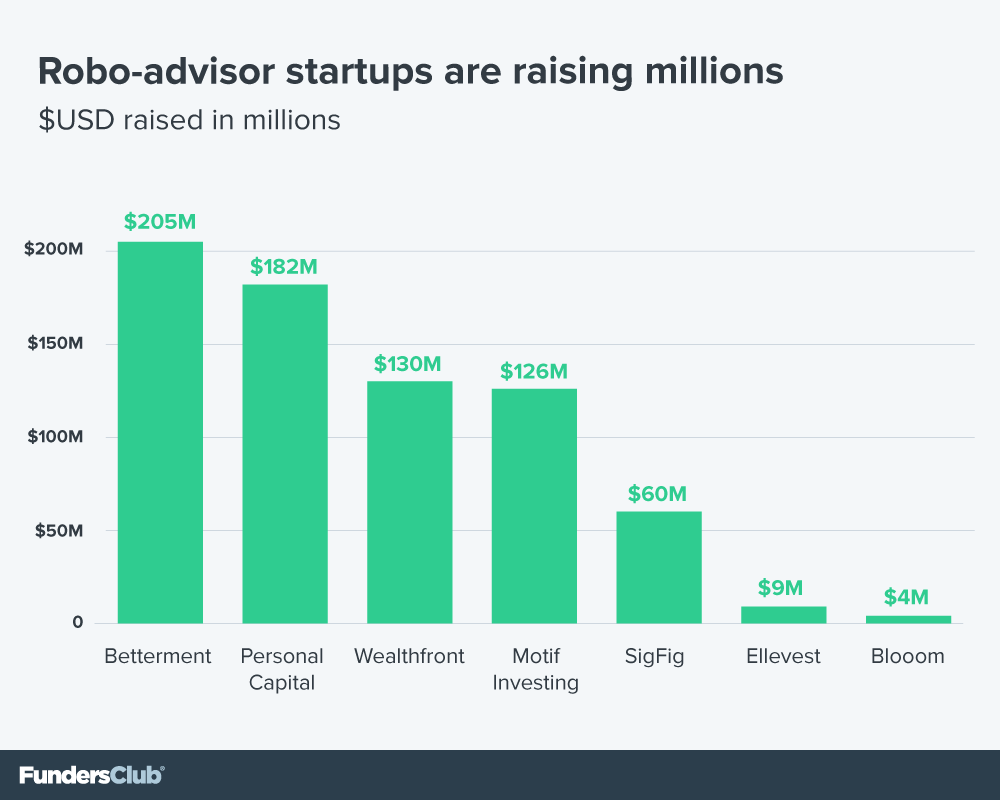

We spoke with the CEOs at Betterment and Wealthfront, and the heads of the robo-investing products at Schwab, Vanguard and Fidelity, among others, to get their takes on the space. All of them offer unsurprisingly positive outlooks on their own futures, and there's little doubt that Betterment and Wealthfront, with $205 million and $130 million raised, stand good chances of surviving what will likely be an expensive competition to recruit more accounts and assets.

Our core findings:

- Wealthfront, Betterment and the other newcomers believe that, like Amazon bested Walmart online, continued innovation will help them win out.

- Schwab and Vanguard see their products as part of an ongoing evolution, and believe human advisor input remains key and desired by many people.

- The robo-advisor movement's roots trace to indexing, which has steadily gained since Vanguard started pushing the products in the 1970s and has become the default investment vehicle for most people.

- There now exist more than 20 robo-advisor products on the market, most of them backed by venture capital. Some of these will not draw a critical mass of users or capital, and will fail.

- The robo-investing startups do not face some of the ethical dilemmas that the incumbents do, as the new companies are fund agnostic. Fidelity, Schwab and Vanguard, of course, would prefer to put consumers into their own funds. As the trend of transparency grows, this favors the startups.

- Acquiring customers in this space is expensive, and the incumbents already have the accounts. This favors the incumbents.

- There are parallels between investing and everything else that has been disrupted by the web, whether it's servers, cloud storage or SaaS. Prices and margins will compress, and competitors will be winnowed.

How did we get here?

During the last year, $310 billion moved out of actively-managed mutual funds where humans decide what equities belong in the fund and $409 billion moved into index funds, which simply track a major index, such as the S&P 500 or the Dow Jones Industrial Average.

This is a continuation of a decades-long trend of an overall shift to indexing by normal investors. The first index fund, started by John C. Bogle at Vanguard in 1975, was derided as backwards and, as it only sought to achieve the index’s average return, unambitious. As it turns out, of course, index averages are difficult to beat. Data has continually shown that 90% or more of actively managed funds fail to outperform indexes across time. Add in the extra costs of that active management—compounded across decades—and the case for indexing has become watertight.

That message has taken years to percolate through to the public, but we're now at a point where Vanguard, still the market leader in low-cost index funds, holds 6% of the value in the U.S. stock markets.

As the virtues of low-cost investing have crystallized, another core strategy that's critical to long-term investment success has gained further notice: diversification and regular rebalancing. Employing this tactic leads investors to stay away from the trap of over-betting on one space or index while also leveraging rebalancing’s effect of selling high and buying low.

The old problem for most people with diversification and rebalancing is that it required time, a calculator and the willingness to investigate which funds are best for the job. While indexing could be easily and passively achieved, rebalancing was only within the purview of proactive investors—and most people aren't.

But an algorithm can easily handle this task. So it was only natural that, once available, that the pairing of low-cost indexing and automatic diversification and rebalancing would become a standard.

Betterment started the trend and remains a leader. Investors valued it at $700 million during its last round of funding; Wealthfront received an equal valuation. Investment in the space peaked in 2014, when $290 million poured in from venture capitalists. At that point, incumbent firms took notice.

Everybody gets a robot

Just as other companies have followed Vanguard into indexes—Fidelity, Schwab, and BlackRock are all major players here—the bigs have all copied the robo-advisor model in some form. Fidelity, Schwab and Vanguard have built their own products, and Blackrock purchased FutureAdvisor in 2015 for $150 million.

Fidelity is newest to the robo-advisor crowd, having just released its Fidelity Go product to the public in July. Fidelity's core business, more so than the rest, has been built on actively managed funds, like its Contrafund, the very theory of which runs anathema to the core ethos at the robo-advisory firms.

In 2015, however, continuing the trend in the industry, Fidelity saw investors remove $18.8 billion from its actively managed funds, even as its overall assets under management increased by $191 billion. Fidelity's popular actively-managed Contrafund, which holds $103 billion with a net expense ratio of .70%, generated around $720 million in revenue by itself for Fidelity in 2015. That kind of circumstance may explain why Fidelity was among the last to adopt a robo-advisor product. The company has been built around active management and the idea that investing is a complicated task.

That fact was clear when I spoke with John Sweeney, the EVP of Retirement and Investment Strategies, who oversees most of Fidelity's digital efforts, including Fidelity Go. Sweeney says Fidelity views the current tidal shift of money toward index funds as cyclical. The company expects that actively-managed funds will stage a comeback in terms of attracted capital at some point, when, over a few years, a larger slice of them outperform the market.

Sweeney and Fidelity still see alpha—defined as the margin by which an investment or trade outperforms the market and the average—as a core objective for the company’s myriad actively managed funds.

This is in stark contrast to how the startups in the space see the market, as they generally believe that beating the indexes for a prolonged period of time is unlikely and, given the cost of active management, not a productive goal.

The case for startups

Companies like Betterment have been built around a tight focus on low costs, diversification and rebalancing. Their missions remain sleek compared with incumbents such as Fidelity and Schwab, which must acknowledge the large revenues provided by legacy businesses, like actively managed funds, while also building new products that mimic what the startups have created.

“I don't discount the fact that a lot of the deep pocketed incumbents will be spending a lot on marketing to convince younger people that they should gamble with an actively managed fund,” says Greg Smith, president at Blooom, a robo-startup focused on 401ks. Smith rather famously penned a scathing New York Times op-ed, and a book, Why I left Goldman Sachs, ripping Wall Street for wittingly ripping off clients.

These inevitable mixed missions at incumbent firms can hamper their ability to fully execute on new products, and curb their will to innovate in new spaces.

"I was there in the 1990s when they said every retailer was going to roll out a website and kill e-retailers," says Adam Nash, CEO of Wealthfront. "But that didn't happen."

Just as Walmart, Target and others didn't quash ecommerce startups with their own sites, broadcast television and cable providers were unable to fight off upstarts who reached consumers through the web. Nash sees the same dynamic in the investment business.

Roger Lee, CEO and co-founder at Human Interest, a startup focused on providing automated 401k plans for employers with a minimum amount of setup and implementation, says newer tech-based companies will always be a step ahead in their user interfaces, which will help insulate their advantage with younger investors. "The user experience gap is real," he says.

That's something that most observers in the early 2000s assumed incumbent retailers would catch up on, but, as Walmart's acquisition of Jet.com shows, it has yet to happen.

"The incumbents would like for nothing more than innovation to stop," Nash adds. "But technology always takes you in new directions"

Nash sees three keystones in the evolution of investing:

- 1. Index funds (1970s)

- 2. The web and the free flow of information (1990s)

- 3. And now the wide availability of automation to investors

Nash expects a higher and higher percentage of investments to be in automated systems as time goes on.

Jon Stein, Betterment's CEO, also thinks that the scope of automation goes far past where it's at now.

"This isn't just about the future of retirement accounts and investing accounts, this is about the future of money," he says. "There's all kinds of complicated ways to get more out of your money - and technology is really good at that."

The breakdown of Americans’ investment accounts, roughly:

- $5 trillion in 401k assets

- $7 trillion in IRA assets

- $5 trillion in taxable mass market accounts

Betterment now has a product aimed at the 401k space, a place where many Americans do the bulk of their savings. The company's move toward a wide quiver of products puts it in competition with more of the traditional financial advisor set.

Stein sees banks in the future becoming more and more like utilities that will be regulated around a set of standards. Programs such as Chase's Private Client, where the bank charges management fees of 1.5% of a person's total portfolio, including cash in their checking and savings accounts, will fall out of favor. Automated software will fill the gap, charging a fraction of the fees. Betterment's current management fee for accounts larger than $100,000 is 0.15%.

Revenues at banks like JP Morgan and Citibank will ebb, as software grinds down margins.

"Advice will become the new central financial relationship," says Stein.

One additional step for robo-advisor startups would be moving into the fund business themselves, creating their own ETFs and index products. Stein, however, would prefer to avoid the conflict now facing companies such as Fidelity and Schwab, who have to choose whether to place their clients' money in their own products or competing ones which may sometimes have lower fees.

"We don't want to be the one manufacturing the products," he says. "It's one of the major points of differentiation between us and the incumbents."

The case for incumbents

"The biggest advantage to Schwab and Fidelity is their install bases," points out Human Interest's Lee.

"But if you look at new acquisition and new install base growth, with young people, it would seem to me that maybe Schwab won't be able to acquire new customers as well as Wealthfront will," Lee adds.

The main challenge then, for incumbents, is one of marketing—getting millennials to recognize and value their names as much as their parents do. But having been reared in a world of startups, where some of the biggest companies in their lives—Airbnb, Uber, etc.—didn't exist seven or eight years ago, millennials' choices as consumers are driven far less by the perceived venerability of any one brand. Just as millennials would likely trust a startup's software to drive their car, they will trust a startup with their money.

The existing user base at incumbents and the money they wield is powerful, however. Vanguard's Personal Advisor Services, which offers users algorithmic control and rebalancing of a portfolio, was launched in May 2015 and now holds $42 billion in assets, the largest total for any robo-product.

Many of the assets in Personal Advisor Services came from existing Vanguard customers, says Karen Risi, managing director of Vanguard's retailer investor group, which includes the automated product.

Vanguard has benefited more than any one company from the investment market's shift toward low-cost index funds, as it owns the lowest cost index product in a number of spaces. Robo-advisors, especially those that are deemed fiduciaries—such as Betterment, Wealthfront, Blooom and Human Interest, often select Vanguard products as primary investment vehicles.

"The role of technology and algorithmic advice is an important one, and I think you're going to see more and more of it," says Vanguard’s Risi.

Vanguard knows it has a secure brand with boomers and pre-retirees, whom it primarily targets, which is why its Personal Advisor product gives users the ability to tap a human for added advice or input. Because of that, Vanguard requires a $50,000 minimum for Personal Advisor accounts, and it takes a management fee of 0.30%.

With that high minimum and its emphasis on available human advisor assistance, Vanguard may be factoring its Personal Advisor product out of many millennials' processes.

"It's a question we ask ourselves all of the time," says Risi.

Given Wealthfront's $500 minimum and Betterment's minimum of $0, Vanguard may have to consider altering its approach.

Flattening of the market

Fees have been getting ground down within the industry for decades, for both actively managed funds and index funds. It will continue to be a focus, and it's likely that minimum balances will follow fees in shrinking further.

Schwab's product in the robo-advisor space, Intelligent Portfolios, charges zero management or account fees to users above those that are included in its underlying index funds. The required minimum investment is $5,000. Schwab uses products and ETFs from 11 different companies, with some of them coming from Vanguard, and many from Schwab itself.

But Schwab’s zero fees declaration has caveats.

Schwab's revenue from its robo-product comes from the investments that sit in its own ETFs and the interest spread it makes on any money held in cash, which it requires every Intelligent Portfolio to contain, from 6% of an account’s total to 30%. And Schwab’s ETFs, in some cases, carry fees 3x as high as those of comparable Vanguard products.

Schwab’s indirect way of getting income from its robo-product has been bashed by Wealthfront’s Nash, who wrote, “For a young investor, Schwab’s greed is expensive. Too expensive.”

Raymond James estimated the real cost of a Schwab Intelligent Portfolio to be .75% annually, making it more expensive than offerings from startups like Nash’s, but this is not a fact readily apparent in Schwab’s marketing that tout its 0% fees.

Like other incumbents, many of the $8.2 billion in assets in Schwab's robo-advisor product came from existing Schwab customers, as three-quarters of the customers within Intelligent Portfolios had some existing relationship with the company.

"We see this product and robo-advice in general as an evolution in this industry, not a revolution," says Tobin McDaniel, president of Schwab Wealth Investment Advisory and head of Schwab Intelligent Portfolios. "It's a major part of our future, but we still think the future will look something like the past."

Trends point to near-zero minimums with near zero incremental fees—but it will remain up to consumers to parse the differences inside of the products, like the non-obvious costs inside of Schwab’s.

That could make progress difficult for startups, especially those that aren't already very well capitalized. Competing in a space that continues to be commoditized with lower fees and lower-value customers doesn't typically excite venture capitalists.

And it may not excite employees who see little differentiation between the product they're working on and the rest of the space. Wealthfront recently lost Eliot Shmukler, its head of product, to Instacart, as well as Brian Dennen, its COO, and Maya Grinberg, its director of marketing.

Marketing will be imperative

Wealthfront and Betterment continue to roll out product features ahead of the incumbents. Wealthfront introduced something it calls direct indexing—where its algorithms actually buy many of the largest underlying stocks in an index for clients in lieu of purchasing an ETF. This allows Wealthfront to sell individual losers within the index and re-buy them, thus capturing the loss for tax purposes. Conventional mutual funds, because of a 1940 law, are unable to distribute losses to individual investors.

That said, it's likely that versions of that feature will pop up at startup competitors as well as incumbents. Wealthfront's engineers and product leaders deserve credit for the innovation, but features like this will unlikely be differentiators within the space for very long.

The question for those who think the startups can gain share based on innovation: How important are incremental improvements that can be easily copied in an industry where most customers’ outlooks span decades, not months or even years?

Millennials and others who desire to put things on a software-enabled autopilot enjoy that kind of proposition exactly because they seek to stay out of the minutiae and arcane side of matters on which they aren't experts. Optimizing tax-loss harvesting and direct indexing then, while they may be impressive technical feats, aren't the kinds of things likely to push an average person to one brand over another.

That means that the robo-advisor battle may come down to a simple marketing scrum, one that takes deep pockets. Among the startups, only Wealthfront and Betterment seem to be capitalized for such a thing, and they'll likely require more cash at some point. The incumbents already have giant line items within their P&Ls for marketing, so it may simply be a question of allocating more toward their robo-products within that budget.

But in pushing more money toward marketing their robo-investment products, the existing behemoths will be putting less marketing toward higher margin products, even though they may be shrinking. It's a tension that will continue to exist at companies such as Fidelity and Schwab, and it's not yet clear that it's a bargain they're willing to make.

Summary

Startups have indelibly changed the market within the investment marketplace. The focus had already shifted toward lower management fees and index funds within the space, but the startups accelerated that movement and then added the twist of automatic rebalancing and automatic portfolio structuring according to goals, age and risk appetite.

It’s this automatic management, with some bespoke factors per user, that may ultimately upend an giant industry that has been built on people, relationships, marketing and sales—all built for the chance to manage people's wealth while taking fees out of it every single year.

Incumbents aren’t crumbling, however. They’re girding for the fight and building their own automation platforms and bots, mimicking the models of the startups. Whether incumbents’ clear preference to inject human advisors into their “automated” products is a true expression of what they consider to be a superior approach, or simply the manifestation of the hopes and demands of the thousands of human advisors currently employed by incumbents remains to be seen.

The real question for the industry is whether there will continue to be a downward squeeze on fees. It’s that movement that has made Vanguard a giant and which led, indirectly, to the rise of the startups. But it’s also this continuing movement that could further commoditize the space, narrowing margins and making it harder to earn back very large customer acquisition costs for startups that greatly lag incumbents’ overall user count and assets under management.

In this environment of growing commoditization, startups seeking sustainability would be wise to bring to the table differentiated business models that go beyond attempting to monetize index investing itself.