AI Can Make Anything a Commodity, Even Creativity

Christopher Steiner co-founded Aisle50, YC S2011, which was acquired by Groupon in early 2015.

We earlier acknowledged that AI isn't actually artificial intelligence. The modern tech lexicon accepts AI as a group of computer-driven methods for mining data, parsing relationships and even, in some cases, creating new things.

So AI shouldn't be judged as whether it can perfectly mimic a human in all phases. To be successful, AI only needs to match—or surpass—humans at particular tasks. It's infrequent that software or a bot will completely replace a human's job role, but two or three different pieces of software can eat away at enough of one's responsibilities that her place in a business process can be handled by other people with lesser educations—or the tasks could be deemed superfluous altogether.

This has always been the tension with software. It can create incredible efficiencies, but it can subvert the very people who employ it, and even the people who create it.

An MIT Technology Review survey found that two-thirds of surveyed HR executives expect to be managing AI talent as well as human talent within five years.

The rise of AI-infused software will eat up all kinds of tasks once deemed intractably human. Accountants, lawyers, writers, marketers, even developers and doctors shouldn't dismiss the notion that they will be working alongside AI that effectively outperforms them at tasks that were once core to their job descriptions.

"The current wave of AI really is revolutionary – but it’s not a race, it’s a marathon," says Jack Berkowitz, VP of products and data science for the adaptive intelligence program at Oracle. "Technology is in the subtle approaches and when we look back ten years from now, we’ll be amazed at all the things that happened."

As AI codifies everything that merits it, the commoditization of many kinds of work will continue. AI itself will become a commodity, a set of methods that can be put into standard packages, sold as software, sewn up and put into easy-to-access APIs.

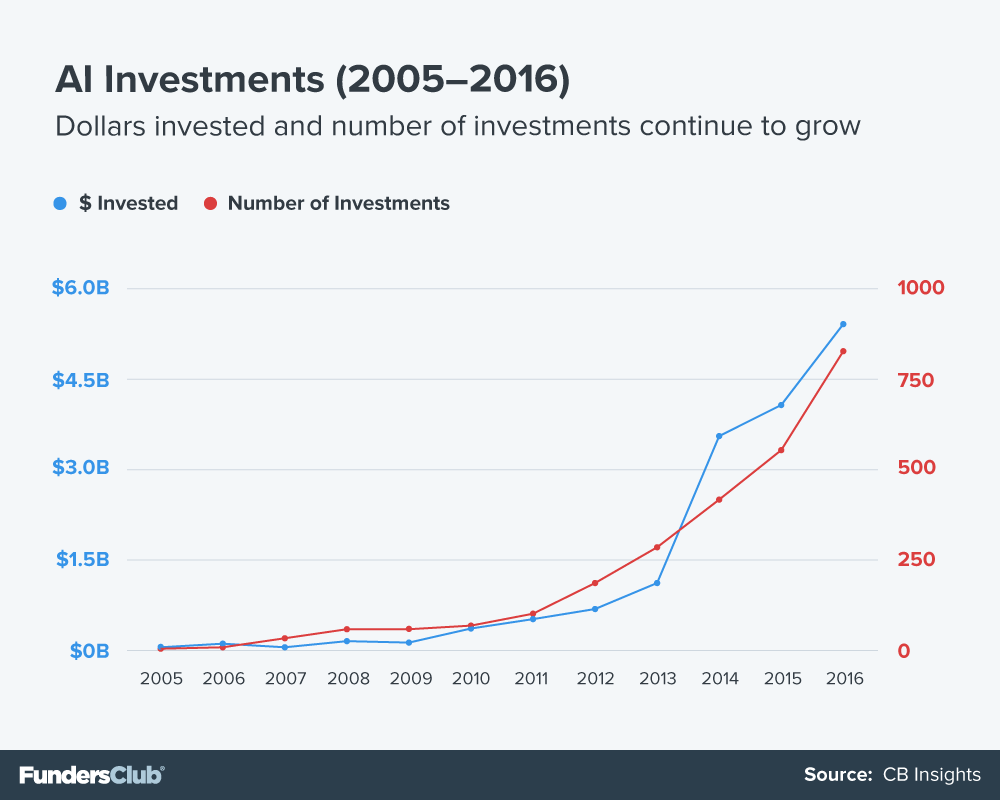

We are already on this path, as the world is creating more and more AI-enhanced software at an accelerating pace. Venture investors have seen AI as one of the next burgeoning sectors of tech, and the money has poured in (see graph).

Startup founders, of course, have noticed this, and have gladly tailored their startups to capital forces and demand, creating more AI companies.

Want to get your startup funded? Add in some AI

Nobody would question whether AI has knitted itself into the current zeitgeist of Silicon Valley and the startup world. Investors, by way of the checks they're writing, are clamoring for it. In 2016, VC and angel investing in companies classified as AI by CB Insights increased 33% to $5.38 billion compared with 2015, and is up 11.2x since 2015.

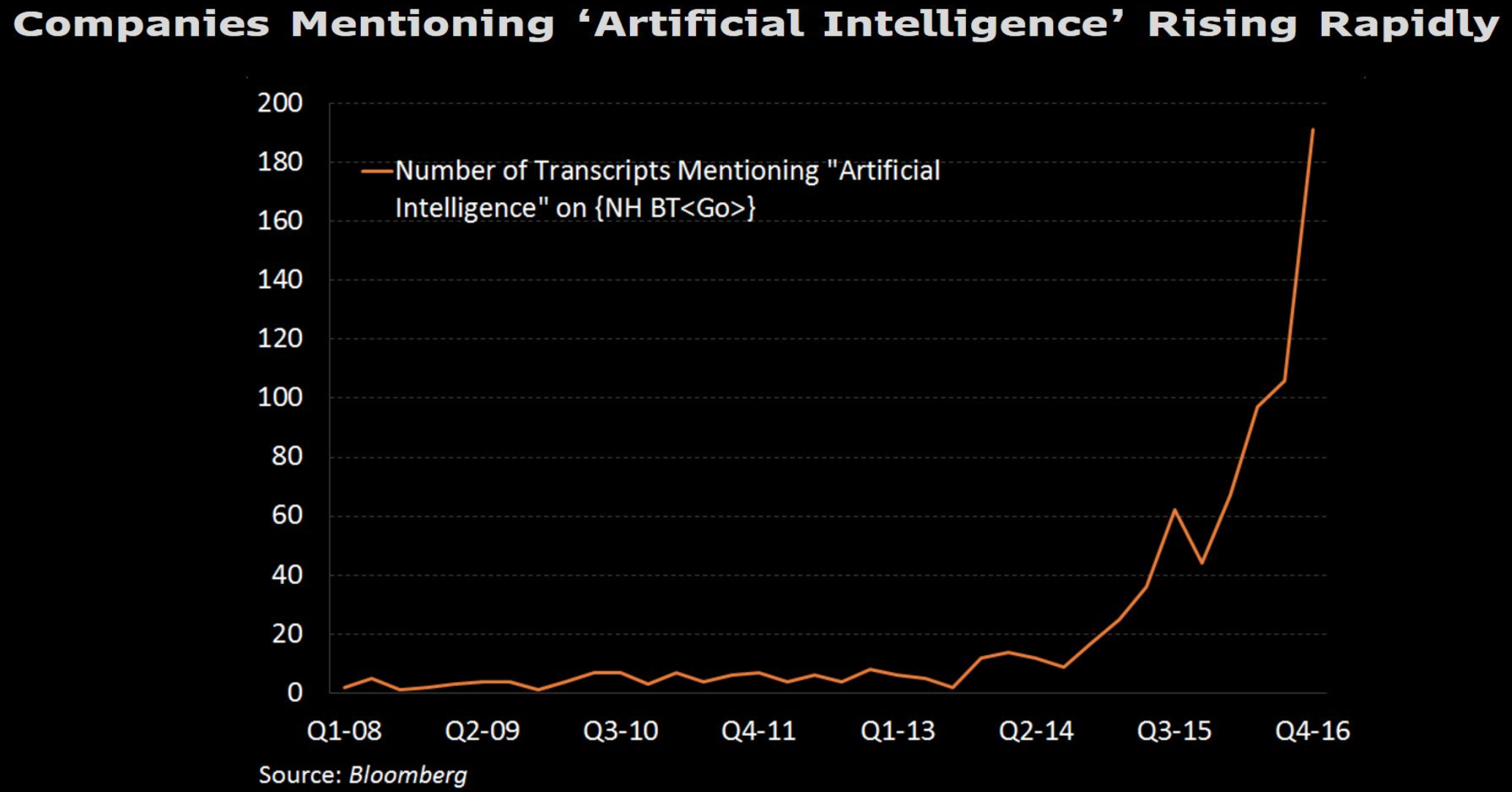

Big companies want in, too. The mention of AI in recorded earnings calls by big public companies, as tracked by Bloomberg, went from 60 per quarter at the end of 2015 to 200 per quarter by the close of 2016.

A valid question: how well-equipped are VCs to vet AI startups? Do most VCs have the aptitude to know or care whether an AI startup has IP vs. pulling AI straight off a shelf—which becomes easier every day. The latter isn't necessarily bad, but VCs and investors should understand that without pairing it with unique and deep domain-specific knowledge, standard AI methods do not comprise and kind of defensible IP or barrier to entry.

The reason for this is simple: standard AI methods have shifted from being a unique product to a commodity.

Most developers with backend experience, given data, can build a machine learning model in a matter of minutes

Those steeped in AI knowledge shouldn't get upset about this statement, as it is by no means claiming that machine learning or any other AI technique is easy to understand, let alone execute and master. But developers not armed with a deep well of knowledge on these things can turn to services and APIs to do it for them. Developers can now upload a giant CSV to AWS and, with a few stipulations, get back a machine learning model, accessible via API, in less than 20 minutes.

And AWS isn't alone in offering these kinds of services. Even image parsing can be had via API as a service from companies such as Clarifai.

The point here is that a startup needn't have a team of people working on AI methods to claim that they're "The dashboard for X, infused with AI." A startup needn't even have a statistician, a data scientist or a single person who knows how to build a model from scratch.

It only needs a front-end and a way to collect money from clients. It's certainly up for debate if such a startup's outsourced AI is any good, but their labeling is legitimate, even if a startup doesn't know how its own model works.

AI will follow the path of the cloud: what was once a novel solution will grow standard

The cloud—and very particular pieces of it, at that—have become so integral to much of the software we use everyday that some people are calling for companies to get off third-party cloud services altogether, to keep themselves separated from web outages that can arise from ubiquitous systems such as that of Amazon's S3. But it's hard to get away from the cloud—as Gitlab's Sean Packham so eloquently explains—with a little help from Hacker News users.

Likewise, it will be hard to get away from AI for any company in the future that deals in data.

It's already hard to avoid AI. Some worry that virtual assistants in the home—25 million will be sold this year compared with 1.7 million in 2015—are having profound effects, not all of them good, on the children who live with them and use them.

As has been well chronicled, the march of self-driving cars is well underway. There will come a day not far in the future when automated vehicles comprise more than half of the cars on a roadway.

Interstate 280, for instance, that hill-coursing stretch of road that connects the back door of Silicon Valley to San Francisco, has already become the asphalt province of AI bots, learning, driving, cruising perfectly down the center of lanes. The roadway is rife with Google’s self-driving cars, Telsa’s bot-assisted sedans, and efforts from any Bay Area company with auto-driving aspirations, and there are a lot of them.

"The road to AI is has been paved by a surge of innovation that has pushed us over the tipping point from research to mainstream use," explains Nidhi Chappell, director of Intel's AI products. "Each new AI algorithmic innovation and use case opens more eyes to the power of AI, leading more innovators to join the community and stimulating an ever-increasing demand for the technology."

Any growing company with reams of data likely applies best practices to storing, backing up, indexing and accessing one of its growing resources—and AI will soon be part of that. An expanding array off-the-shelf solutions will continue to grow more robust and more effective in teasing more insight out of the same data.

Interest in AI has peaked before, of course. But the combination of so much clean data and far more powerful computing options, including common APIs and standards, means that instead of peaking out as a fad, AI will become a just another standard in the computer science toolbox.

Even creativity will succumb to the forces of AI

Some people who fear for the bot takeover of jobs and the economy take some solace in the notion that AI won't be able to reach into the creative economy, that it's these jobs where AI can't compete, can't comprehend.

But these are bad assumptions.

The first mistake many people make when thinking about creativity is assigning it, as a process, some kind of magical quality, some kind of nebulous, non-quantifiable property that can only be kindled inside a human brain. But creativity doesn't happen in a vacuum. We don't produce ideas from scratch. We iterate on the creativity of others, whether it's as writers, composers, coders, scientists, artists, whatever.

A company called Narrative Science, in Chicago, creates algorithms that produce original works of journalism in a number of spheres. If you read financial news, you’ve likely read an earnings report on a public company that was penned by an algorithm.

Many news outlets, such as the AP and Bloomberg, dedicate humans to writing earnings reports on blue chip companies such as Exxon, Google and Apple.

But thousands of mid-market companies exist—companies worth billions of dollars—where assigning a human to cover earnings can be cost prohibitive. In some cases, the bots belonging to Narrative Science handle the task. The company’s algorithms take in the same information a human does—the numbers in a 10Q or 10K, the document’s notes, the background news and facts—and produce an original journalistic piece that reads smoothly.

Narrative Science got its start by producing algorithms that wrote news pieces based on sports box scores, baseball in particular, where most of the story is told by the data.

Beyond words, we may well see a day when movie scores are quickly ginned up by AI programs seeking input on: the genre of movie, the type of music desired, the number of suspenseful scenes, etc. This sounds fanciful, but it’s almost certainly in the offing. Who gets in the movie credits for that? The algorithm? The engineer?

A company called Amper just raised $4 million to use AI to write music. Is this ‘Peak AI’ ? Probably not.

Forms of AI have been making music—some of it great—for decades. The process of making this happen, however, has simply grown far easier as banks of data and computing power have grown exponentially cheaper and more available.

David Cope, a computer science and music professor emeritus at the University of California, Santa Cruz, spent more than half a decade building a dataset of Bach music large enough to facilitate the creation of new classical music by an algorithm he had created. This was in the 1980s. Some of the music that Cope's early bot produced is hauntingly human.

But the work that took Cope, who has a brilliant mind that nimbly dances back and forth from musician to engineer, years of grinding might only take him months or weeks now, given the tools, computing and data available.

If creating quality original music isn't creative, then what qualifies? Perhaps that's a question for Alexa.